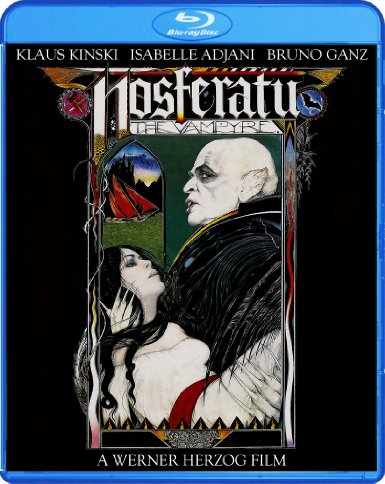

Nosferatu the Vampyre by Werner Herzog

The Most Abject Pain

Werner Herzog grew up in the Bavarian Alps without running water, a flush toilet or a telephone. When he was young he was eager to make movies, so he stole a camera from the Munich Film School, claiming he had some sort of natural right for a camera, a tool to work with. As a full-fledged artist he promised to eat his own shoe if his friend completed a film.

And he kept his promise.

When the film premiered he boiled his shoes and ate one of them in front of the audience.

While making Fitzcarraldo, Herzog and his crew, together with indigenous Amazonian Indians, hauled a three-story 320-ton steamship up a muddy 40-degree hillside in the jungle. Somebody asked Herzog if it wouldn’t be wiser to quit. How can you ask this question? he snapped. If I abandoned this project, I would be a man without dreams, and I don’t want to live like that. I live my life or I end my life with this project. … Without dreams, we would be cows in a field.

In 1979 Herzog made Nosferatu the Vampyre, a remake of F.W. Murnau’s classic Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922), itself an adaptation of Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula (1897).

Remaking a famous vampire movie is, of course, a formidable challenge. First, how do you improve on a masterpiece that Herzog himself considers the greatest German film of all time? Second, how do you breathe new life into the vampire movie with all its inanities like neck biting and bloodsucking, ubiquitous coffins and inescapable graveyards, disturbed pale-faced women and noble if slow-witted men? And finally: Why on earth would Werner Herzog, a world-class arthouse director, want to waste his time on remakes and dubious genres?

Some filmmakers, e.g. Roman Polański in his mischievous comedy The Fearless Vampire Killers, Or Pardon Me, But Your Teeth Are In My Neck (1967), Mel Brooks in the zany farce Dead and Loving It (1995) and Robert Rodriguez in the entertaining spoof From Dusk Till Dawn (1996) mock the genre’s conventions, on the ground that there is nothing wrong with the vampire movie, unless it’s taken seriously. But Herzog made it clear that he intended to make a reasonably serious art film about the most famous vampire of them all, Count Dracula, aka Nosferatu. He also added that the vampire genre… means an intensive, almost dreamlike stylization on screen and… is one of the richest and most fertile cinema has to offer. There is fantasy, hallucination, dreams and nightmares, visions, fear and, of course, mythology.

The intensive, almost dreamlike stylization is evident even in the opening scene with the creepy music by the Krautrock band Popol Vuh. If you listen carefully, moreover, you will hear heartbeats in the background. The camera tracks across a row of mummified bodies (victims of an 1833 cholera epidemic) in the Mummies’ Museum in Mexico. Their dramatic gestures and pained faces, frozen in time, imply that these people died in terror, possibly in agony, as victims of a vampire might. Cut to the slow-motion footage of a bat in midair, a vaguely ominous image that will recur several times. Cut to the bedroom: A young woman, Lucy Harker (Isabelle Adjani), suddenly wakes from a nightmare and lets out a blood-curdling scream. Her husband, Jonathan Harker (Bruno Ganz), calms her down, but we already know that something terrible is about to happen.

Motifs of death and terror in the early scenes mingle with images of peaceful, well-ordered bourgeois life. The action takes place in nineteenth-century Wismar, Germany, here played, if that’s the word, by Delft, a charming Dutch town famous for – what else? – canals as well as for blue-and-white pottery and the great painter Johannes Vermeer. The stage is all set for evil to invade. The love, the happiness, the romantic strolls by the sea, the kittens romping in the kitchen – this idyll will soon turn into a living hell.

As the film goes on things become increasingly gloomy. Witness the scene where Jonathan walks to the Castle of Dracula in the Carpathian Mountains, in Transylvania.

The landscape is permeated with an indescribable something which presages doom. The peaks, the chasms and the wooded slopes are cloaked in swirling mists. The waterfalls tumble into turbulent streams amid walls of sheer rock and monstrous boulders, and the looming ruins of a castle or palace dissolve into the dusk. The line between dream and “reality,” as usual with Herzog, is blurred. Popol Vuh’s somber chant gives way to the spine-tingling Prelude (Vorspiel) to Richard Wagner’s Das Rheingold. An ornate coach, similar to those we know from fairy tales, appears like a phantom, and takes Jonathan to the castle. These remarkable scenes with no action or dialogue were filmed in various locations: the mountains in the High Tatras in Slovakia; the Borgo Pass in the Partnach Gorge in Bavaria, Germany; the Castle of Dracula at the Pernstejn Castle in the Czech Republic.

The plot thickens when Jonathan dines in the castle. Count Dracula, a deathly pale, rat-toothed creature, looks like a giant rodent or spider, and his stupendously long claws seem even longer when he pours wine for Jonathan.

Suddenly…

A strange grinding noise breaks the silence, and the camera cuts to a wall clock crowned with a skull. The top of the skull opens like a coffin lid, a miniature blacksmith appears and begins to strike the anvil with a hammer. The door below the clock opens too and the Grim Reaper comes out. On the stroke of midnight the skull’s “lid” slams shut, raising a cloud of dust. Jonathan, numb with fear, cuts his thumb slicing bread, Dracula offers the oldest remedy in the world (The knife is old and could be dirty. It could give you blood poisoning) – an offer Jonathan can’t refuse – and the rest is easy to imagine.

The real in Herzog’s movies often blends with the unreal, and the physical with the metaphysical. Try Lucy’s first encounter with Dracula.

The door to Lucy’s room creaks open and a spooky shadow appears, first in the mirror, then on the wall. Finally Dracula materializes and discusses philosophy with Lucy – how German is that? At one point Lucy holds forth on the power and cruelty of death. But Count Dracula, no mean expert on the subject, argues that Death is not everything. It’s more cruel not to be able to die, and adds: The absence of love is the most abject pain.

Herzog’s Dracula is not your typical soulless vampire from run-of-the-mill horror movies. He is, in fact, a complex and tragic figure. He is sufficiently human to yearn for love, for example, but not human enough to have it. In essence he is caught between life and death, desire and fulfillment, reality and dream. To compound his misery he cannot die. At one point he says to Jonathan, in a tormented voice: Can you imagine enduring centuries… experiencing each day the same futile things? Precisely. Question to all you transhumanists and immortality enthusiasts out there: What do you say to that?

Even more startling is the thoroughly surreal scene where Lucy walks across the town square among people afflicted with the plague. It’s difficult to tell whether what we can see here is a crazed party for the doomed or one of Lucy’s recurring nightmares. Either way it’s a topsy-turvy world, in which the natural order of things was overthrown by evil.

Coffins with plague victims are scattered all over the cobblestones; a hooded monk (Werner Herzog) prays on his knees; drunken or deranged revelers play and dance with wild abandon; a weird fellow tries to ride, or mate with, a goat among the smoking bonfires; pigs wander the square, defecating; hordes of rats are busy spreading disease. Several townspeople invite Lucy to join them at a well-laden table (It’s our last supper. We’ve all caught the plague. We must enjoy each day that’s left). All of a sudden everything vanishes like a dream. The only thing left is the table swarming with rats.

Count Dracula has outstayed his welcome in Wismar, that’s for sure. But how to get rid of him?

Lucy finds the answer in an old book on vampires – if a pure-hearted woman diverts him from the cry of the cock, the first light of day will obliterate him – and lures Dracula into her bedroom.

Lucy lies on a white bed strewn with flowers. The vampire, spellbound, feasts his eyes on her, and even tries to make love to her. But she pulls him close to make him suck her blood. Predictably they both die at the crack of dawn, Dracula writhing in agony, Lucy with a smile on her lips. Soon after Doctor Van Helsing (Walter Ladengast) appears and drives a stake of aspen wood through Dracula’s heart. The Count has finally found peace in death. But the brave woman that destroyed him will become a zombie because the absent-minded Doctor didn’t stab her through the heart.

Final scene: Jonathan morphs into a vampire, orders the servants to bring him his horse and says that he has much to do now. A while later he gallops across a sandy plain, under a lowering sky, to the solemn sounds of Sanctus from Gounod’s St. Cecilia Mass. Before you know it he will found an investment bank, a brokerage house, an insurance company, or some other reputable firm. He will make you work for him. He will make you prosperous. Like him, you will turn into a whole different creature. Finally, out of gratitude for his kindness, you will beg him to make you immortal, too.

Everything, in the end, goes pitch-black. Welcome to the land of Nothing.

One of the most beautiful, bizarre and haunting films I’ve seen.

© by Krzysztof Mąkosa

Director: Werner Herzog

Starring: Klaus Kinski (Count Dracula), Isabelle Adjani (Lucy Harker), Bruno Ganz (Jonathan Harker)

Supporting actors: Roland Topor (Renfield), Walter Ladengast (Doctor Van Helsing), Dan van Husen (Warden), Martje Grohmann (Mina), et al.