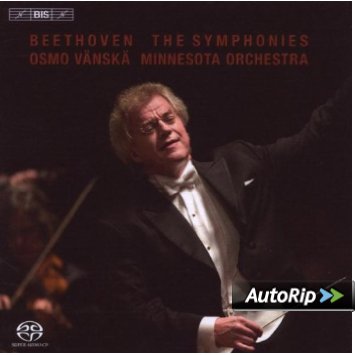

Beethoven symphonies, Minnesota SO/Osmo Vänskä

Very much of and for our own time?

Faced with complementary feeding stuff for cats or pet medication camouflaged with chunks of yummy food, my cat Gustav (“Goosh”) gives it a careful look and a long sniff. Finally, he paws the floor in disgust and struts away. That is also what I do (well, more or less) when it comes to blurbs, puffs, and other marketing gimmicks.

But this time I thought I couldn’t ignore so much extravagant praise from so many respectable quarters. The Gramophone, for example, gushed, One of the finest available Beethoven symphony cycles… a Beethoven reforged for today’s world…; the American Record Guide enthused, It’s hard to think of a more distinguished Beethoven cycle by an American orchestra since the legendary Toscanini traversal of 1939… very much of and for our own time…; and the New York Times opined, It may be the definitive one of our time… the hook is less the latest surround technology than the exciting, involved playing.

Now, I must admit I bought all the hype, and, with it, this much-trumpeted set. And when I was listening to these taut, fleet-footed, well-engineered and unrelievedly bland readings, it suddenly hit me that the reviews were right on point: This Beethoven symphony cycle is, beyond any doubt, very much of and for our own time or, better still, for today’s world, and it may very well be the definitive one for the first half of the 21st century. In fact, the longer I listened, the more convinced I was that Vänskä, a first-rate conductor with several fine Sibelius recordings under his belt, had approached his job with all the passion of a watchmaker or pharmacist. But then, to be fair, I find it hard to blame him for ensuring the two things required from artists these days – thorough preparation and flawless execution. Who could ask for more? Isn’t that what we require from all professionals, including ourselves?

Or maybe Vänskä should have said to the orchestra, Look, let’s not kid ourselves – no matter how hard we try, there’s no way we can beat the Berlin Phil or the Vienna Phil on their home turf. We’re no match for that relentless martinet Toscanini and his impeccably drilled outfit, or his disciple Szell and that perfectly honed machine, the Cleveland Orchestra. We won’t outplay Carlos Kleiber and the incredible Vienna Philharmonic in the Fifth’s Allegro con brio or the Seventh’s Presto. Besides, we don’t want to imitate Gardiner, Harnoncourt, Norrington, Hogwood or Immerseel and produce some sort of beefed-up Haydn, or Pergolesi on speed. C’mon, let’s play the socks off these warhorses with the passion, pride, defiance and dignity they’re crying out for.

And yet, like Gardiner or Harnoncourt before him, Vänskä put his Beethoven on a low-cal diet, opting for brisk tempi, lean sound, transparent textures, strict rhythmic discipline, and precise articulation. While his is a perfectly valid approach, we should keep in mind that there is nothing original or interesting about it. Toscanini and Szell, both of whom had tried these methods long before the so-called authentic performance movement came to the fore, achieved much more in the way of orchestral virtuosity and expressive power.

In any case, if you look for poetry in music, you’ll find it not in box sets, but on individual CDs, such as Carlos Kleiber’s Fifth and Seventh with the Vienna Philharmonic (Deutsche Grammophon), superlative in every way; Fricsay’s exceptionally well played and sung Ninth with the Berlin Philharmonic & St. Hedwig’s Cathedral Choir (Deutsche Grammophon); Monteux’s incandescent Third with the Concertgebouw Orchestra (Philips); Böhm’s spine-tingling Sixth with the Vienna Philharmonic (Deutsche Grammophon); and various other recordings, too numerous to mention here.

But if you feel you must own a Beethoven symphony cycle, try the 1966 Szell-Cleveland SO (Sony), the 1977 (or 1963) Karajan-Berlin Philharmonic (Deutsche Grammophon), the 1989 Wand-NDR, or the 1999 Barenboim-Staatskapelle Berlin (Warner Classics). Unless you’re squeamish about dated mono sound, you might want to consider the remastered Bruno Walter set (United Archives or Music & Arts), featuring eight symphonies performed by the New York Philharmonic and the Sixth by the Philadelphia Orchestra at its most fabulous.

Or stick with this set if you like your Beethoven lean, sterile, and bleached of emotion.

© by Krzysztof Mąkosa